The Poisson Distribution And Poisson Process Explained

A straightforward walk-through of a useful statistical concept

A tragedy of statistics in most schools is how dull it’s made. Teachers spend hours wading through derivations, equations, and theorems, and, when you finally get to the best part — applying concepts to actual numbers — it’s with irrelevant, unimaginative examples like rolling dice. This is a shame as stats can be enjoyable if you skip the derivations (which you’ll likely never need) and focus on using the ideas to solve interesting problems.

In this article, we’ll cover Poisson Processes and the Poisson distribution, two important probability concepts. After highlighting only the relevant theory, we’ll work through a real-world example, showing equations and graphs to put the ideas in a proper context.

Poisson Process

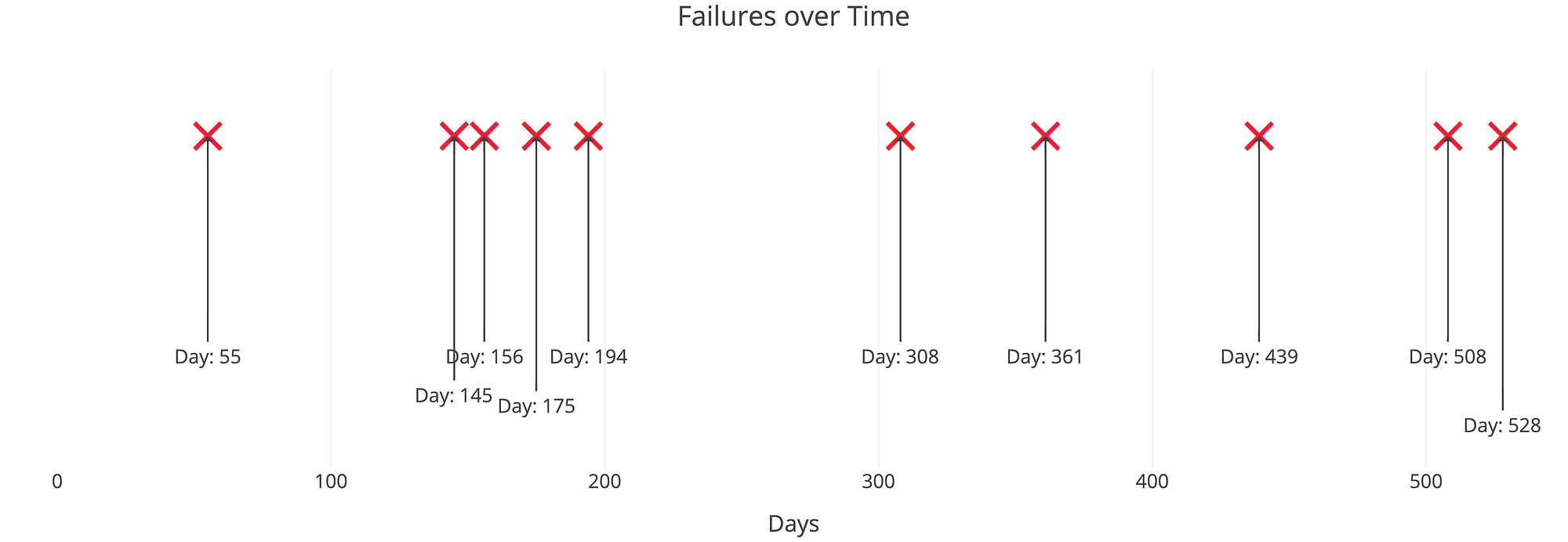

A Poisson Process is a model for a series of discrete event where the average time between events is known, but the exact timing of events is random. The arrival of an event is independent of the event before (waiting time between events is memoryless). For example, suppose we own a website which our content delivery network (CDN) tells us goes down on average once per 60 days, but one failure doesn’t affect the probability of the next. All we know is the average time between failures. This is a Poisson process that looks like:

Example Poisson Process with average time between events of 60 days.

Example Poisson Process with average time between events of 60 days.

The important point is we know the average time between events but they are randomly spaced (stochastic). We might have back-to-back failures, but we could also go years between failures due to the randomness of the process.

A Poisson Process meets the following criteria (in reality many phenomena modeled as Poisson processes don’t meet these exactly):

- Events are independent of each other. The occurrence of one event does not affect the probability another event will occur.

- The average rate (events per time period) is constant.

- Two events cannot occur at the same time.

The last point — events are not simultaneous — means we can think of each sub-interval of a Poisson process as a Bernoulli Trial, that is, either a success or a failure. With our website, the entire interval may be 600 days, but each sub-interval — one day — our website either goes down or it doesn’t.

Common examples of Poisson processes are customers calling a help center, visitors to a website, radioactive decay in atoms, photons arriving at a space telescope, and movements in a stock price. Poisson processes are generally associated with time, but they do not have to be. In the stock case, we might know the average movements per day (events per time), but we could also have a Poisson process for the number of trees in an acre (events per area).

(One instance frequently given for a Poisson Process is bus arrivals (or trains or now Ubers). However, this is not a true Poisson process because the arrivals are not independent of one another. Even for bus systems that do not run on time, whether or not one bus is late affects the arrival time of the next bus. Jake VanderPlas has a great article on applying a Poisson process to bus arrival times which works better with made-up data than real-world data.)

Poisson Distribution

The Poisson Process is the model we use for describing randomly occurring events and by itself, isn’t that useful. We need the Poisson Distribution to do interesting things like finding the probability of a number of events in a time period or finding the probability of waiting some time until the next event.

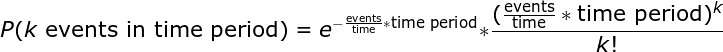

The Poisson Distribution probability mass function gives the probability of observing k events in a time period given the length of the period and the average events per time:

Poisson distribution for probability of k events in time period.

Poisson distribution for probability of k events in time period.

This is a little convoluted, and events/time * time period is usually simplified into a single parameter, λ, lambda, the rate parameter. With this substitution, the Poisson Distribution probability function now has one parameter:

Poisson distribution probability of k events in an interval.

Poisson distribution probability of k events in an interval.

Lambda can be thought of as the expected number of events in the interval. (We’ll switch to calling this an interval because remember, we don’t have to use a time period, we could use area or volume based on our Poisson process). I like to write out lambda to remind myself the rate parameter is a function of both the average events per time and the length of the time period but you’ll most commonly see it as directly above.

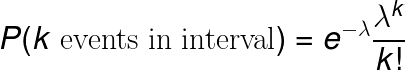

As we change the rate parameter, λ, we change the probability of seeing different numbers of events in one interval. The below graph is the probability mass function of the Poisson distribution showing the probability of a number of events occurring in an interval with different rate parameters.

Probability Mass function for Poisson Distribution with varying rate parameter.

Probability Mass function for Poisson Distribution with varying rate parameter.

The most likely number of events in the interval for each curve is the rate parameter. This makes sense because the rate parameter is the expected number of events in the interval and therefore when it’s an integer, the rate parameter will be the number of events with the greatest probability.

When it’s not an integer, the highest probability number of events will be the nearest integer to the rate parameter, since the Poisson distribution is only defined for a discrete number of events. The discrete nature of the Poisson distribution is also why this is a probability mass function and not a density function. (The rate parameter is also the mean and standard deviation of the distribution, which do not need to be integers.)

We can use the Poisson Distribution mass function to find the probability of observing a number of events over an interval generated by a Poisson process. Another use of the mass function equation — as we’ll see later — is to find the probability of waiting some time between events.

A Worked-Out Example

For the problem we’ll solve with a Poisson distribution, we could continue with website failures, but I propose something grander. In my childhood, my father would often take me into our yard to observe (or try to observe) meteor showers. We were not space geeks, but watching objects from outer space burn up in the sky was enough to get us outside even though meteor showers always seemed to occur in the coldest months.

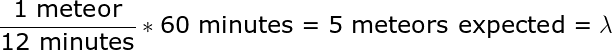

The number of meteors seen can be modeled as a Poisson distribution because the meteors are independent, the average number of meteors per hour is constant (in the short term), and — this is an approximation — meteors don’t occur simultaneously. To characterize the Poisson distribution, all we need is the rate parameter which is the number of events/interval * interval length. From what I remember, we were told to expect 5 meteors per hour on average or 1 every 12 minutes. Due to the limited patience of a young child (especially on a freezing night), we never stayed out more than 60 minutes, so we’ll use that as the time period. Putting the two together, we get:

Rate parameter for the meteor shower situation.

Rate parameter for the meteor shower situation.

What exactly does “5 meteors expected” mean? Well, according to my pessimistic dad, that meant we’d see 3 meteors in an hour, tops. At the time, I had no data science skills and trusted his judgment. Now that I’m older and have a healthy amount of skepticism towards authority figures, it’s time to put his statement to the test. We can use the Poisson distribution to find the probability of seeing exactly 3 meteors in one hour of observation:

Probability of observing 3 meteors in 1 hour.

Probability of observing 3 meteors in 1 hour.

14% or about 1/7. If we went outside every night for one week, then we could expect my dad to be right precisely once! While that is nice to know, what we are after is the distribution, the probability of seeing different numbers of meteors. Doing this by hand is tedious, so we’ll use Python — which you can see in this Jupyter Notebook — for calculation and visualization.

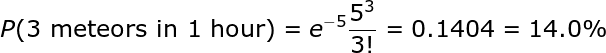

The below graph shows the Probability Mass Function for the number of meteors in an hour with an average time between meteors of 12 minutes (which is the same as saying 5 meteors expected in an hour).

Probability Mass Function of the Poisson Distribution for meteors in 1 hour

Probability Mass Function of the Poisson Distribution for meteors in 1 hour

This is what “5 expected events” means! The most likely number of meteors is 5, the rate parameter of the distribution. (Due to a quirk of the numbers, 4 and 5 have the same probability, 18%). As with any distribution, there is one most likely value, but there are also a wide range of possible values. For example, we could go out and see 0 meteors, or we could see more than 10 in one hour. To find the probabilities of these events, we use the same equation but this time calculate sums of probabilities (see notebook for details).

We already calculated the chance of seeing exactly 3 meteors as about 14%. The chance of seeing 3 or fewer meteors in one hour is 27% which means the probability of seeing more than 3 is 73%. Likewise, the probability of more than 5 meteors is 38.4% while we could expect to see 5 or fewer meteors in 61.6% of observation hours. Although it’s small, there is a 1.4% chance of observing more than 10 meteors in an hour!

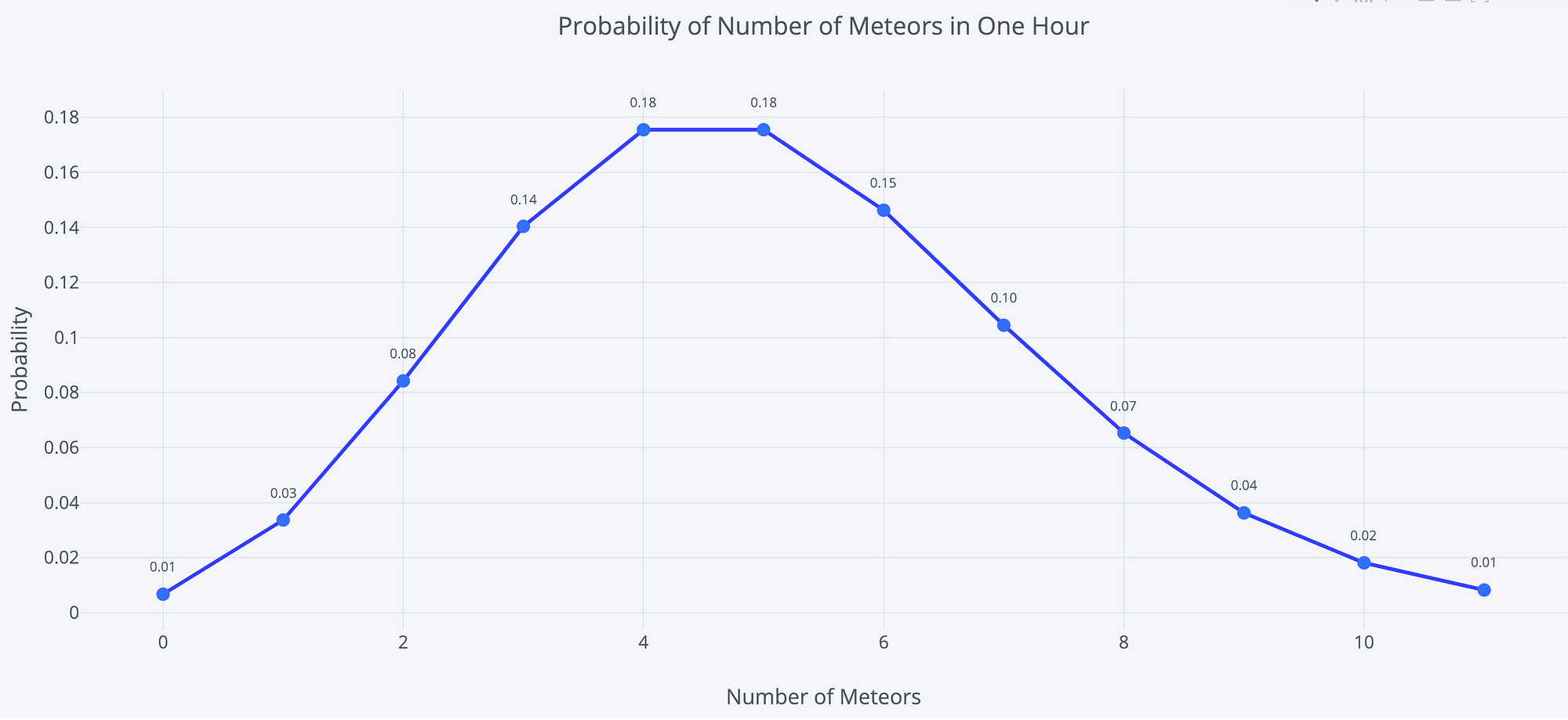

To visualize these possible scenarios, we can run an experiment by having our sister record the number of meteors she sees every hour for 10,000 hours. The results are shown in the histogram below:

Simulating 10,000 hours of meteor observations.

Simulating 10,000 hours of meteor observations.

(This is obviously a simulation. No sisters were employed for this article.) Looking at the possible outcomes reinforces that this is a distribution and the expected outcome does not always occur. On a few lucky nights, we’d witness 10 or more meteors in an hour, although we’d usually see 4 or 5 meteors.

Experimenting with the Rate Parameter

The rate parameter, λ, is the only number we need to define the Poisson distribution. However, since it is a product of two parts (events/interval * interval length) there are two ways to change it: we can increase or decrease the events/interval and we can increase or decrease the interval length.

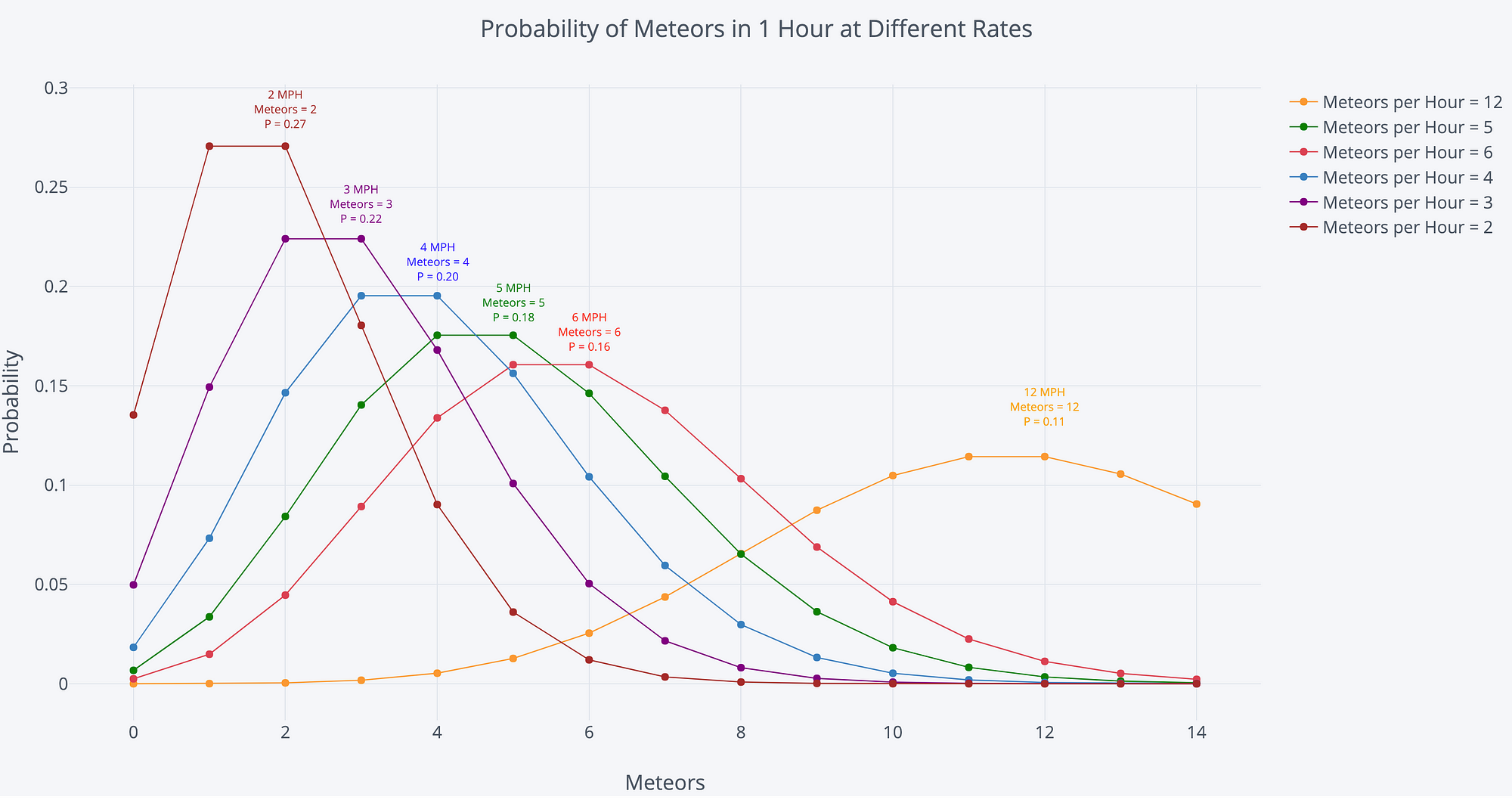

First, let’s change the rate parameter by increasing or decreasing the number of meteors per hour to see how the distribution is affected. For this graph, we are keeping the time period constant at 60 minutes (1 hour).

Poisson Probability Distribution for meteors in 1 hour with different rate parameters, lambda

Poisson Probability Distribution for meteors in 1 hour with different rate parameters, lambda

In each case, the most likely number of meteors over the hour is the expected number of meteors, the rate parameter for the Poisson distribution. As one example, at 12 meteors per hour (MPH), our rate parameter is 12 and there is an 11% chance of observing exactly 12 meteors in 1 hour. If our rate parameter increases, we should expect to see more meteors per hour.

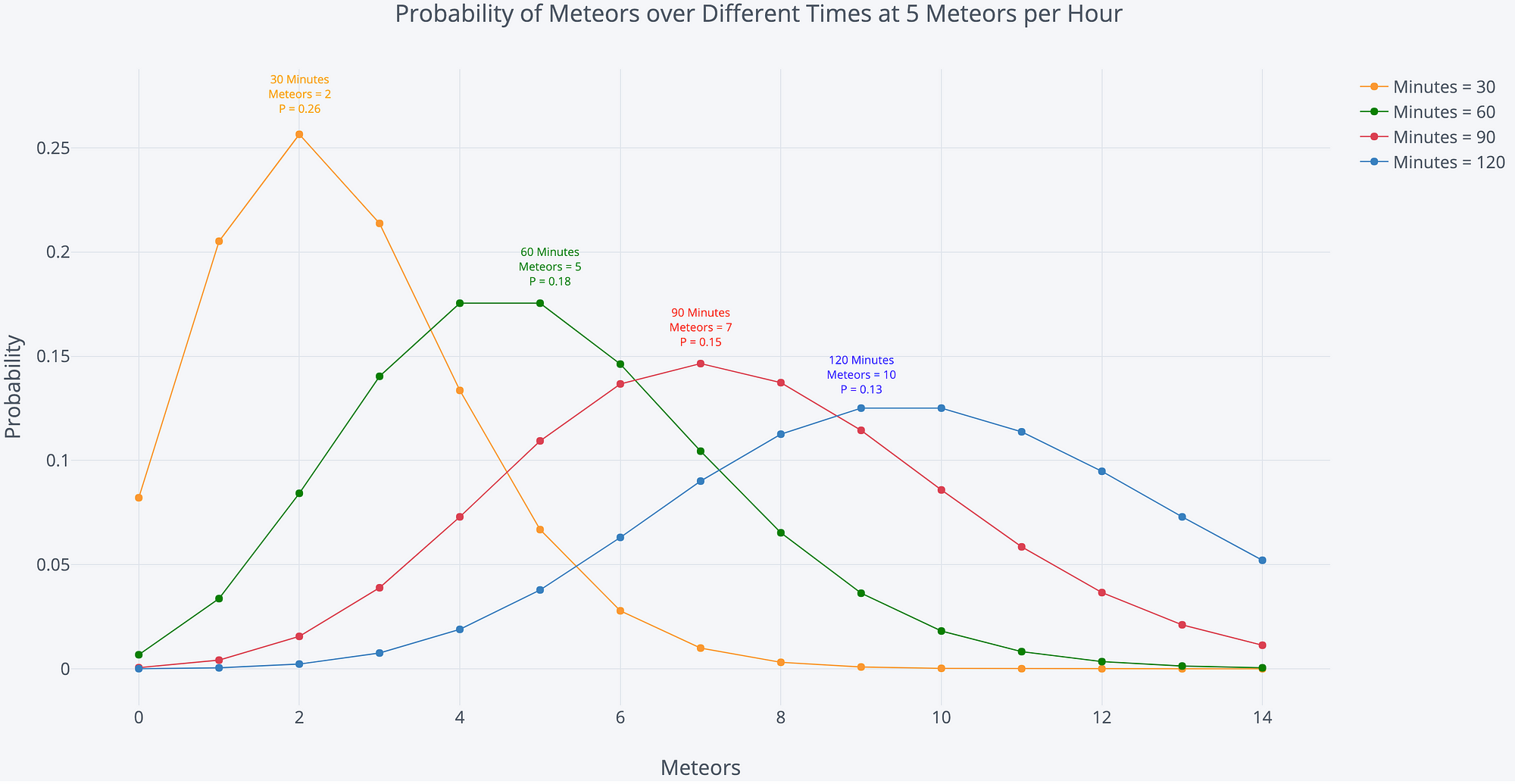

Another option is to increase or decrease the interval length. Below is the same plot, but this time we are keeping the number of meteors per hour constant at 5 and changing the length of time we observe.

Poisson Probability Distribution for Meteors in different lengths of time.

Poisson Probability Distribution for Meteors in different lengths of time.

It’s no surprise that we expect to see more meteors the longer we stay out! Whoever said “he who hesitates is lost” clearly never stood around watching meteor showers.

Waiting Time

An intriguing part of a Poisson process involves figuring out how long we have to wait until the next event (this is sometimes called the interarrival time). Consider the situation: meteors appear once every 12 minutes on average. If we arrive at a random time, how long can we expect to wait to see the next meteor? My dad always (this time optimistically) claimed we only had to wait 6 minutes for the first meteor which agrees with our intuition. However, if we’ve learned anything, it’s that our intuition is not good at probability.

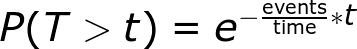

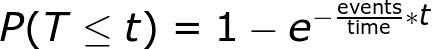

I won’t go into the derivation (it comes from the probability mass function equation), but the time we can expect to wait between events is a decaying exponential. The probability of waiting a given amount of time between successive events decreases exponentially as the time increases. The following equation shows the probability of waiting more than a specified time.

Probability of waiting more than a certain time.

Probability of waiting more than a certain time.

With our example, we have 1 event/12 minutes, and if we plug in the numbers we get a 60.65% chance of waiting > 6 minutes. So much for my dad’s guess! To show another case, we can expect to wait more than 30 minutes about 8.2% of the time. (We need to note this is between each successive pair of events. The waiting times between events are memoryless, so the time between two events has no effect on the time between any other events. This memorylessness is also known as the Markov property).

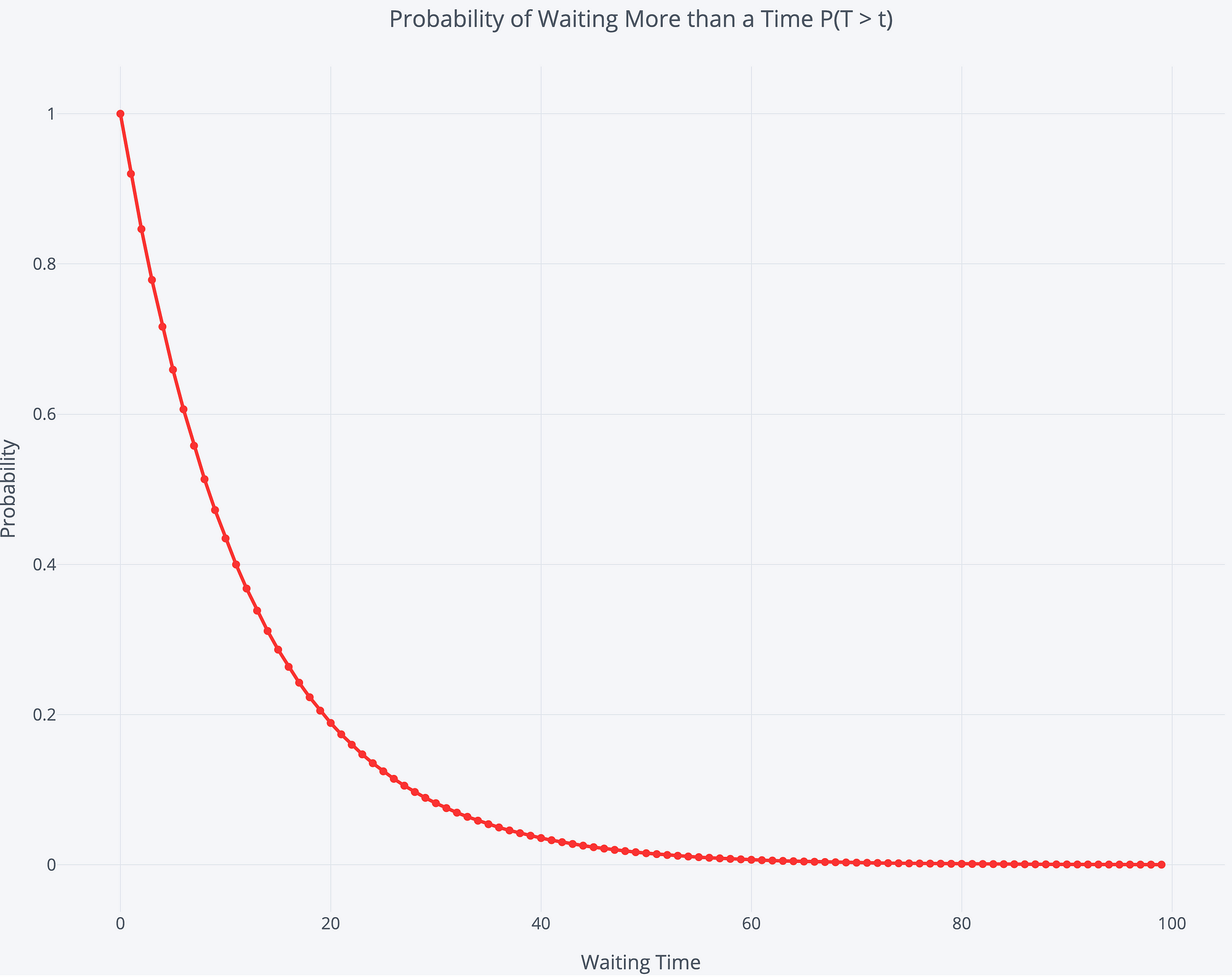

A graph helps us to visualize the exponential decay of waiting time:

Exponentially Decaying Probability of Waiting Time between successive events

Exponentially Decaying Probability of Waiting Time between successive events

There is a 100% chance of waiting more than 0 minutes, which drops off to a near 0% chance of waiting more than 80 minutes. Again, since this is a distribution, there are a wide range of possible interarrival times.

Conversely, we can use this equation to find the probability of waiting less than or equal to a time:

Probability of waiting less than or equal to a specified time.

Probability of waiting less than or equal to a specified time.

We can expect to wait 6 minutes or less to see a meteor 39.4% of the time. We can also find the probability of waiting a period of time: there is a 57.72% probability of waiting between 5 and 30 minutes to see the next meteor.

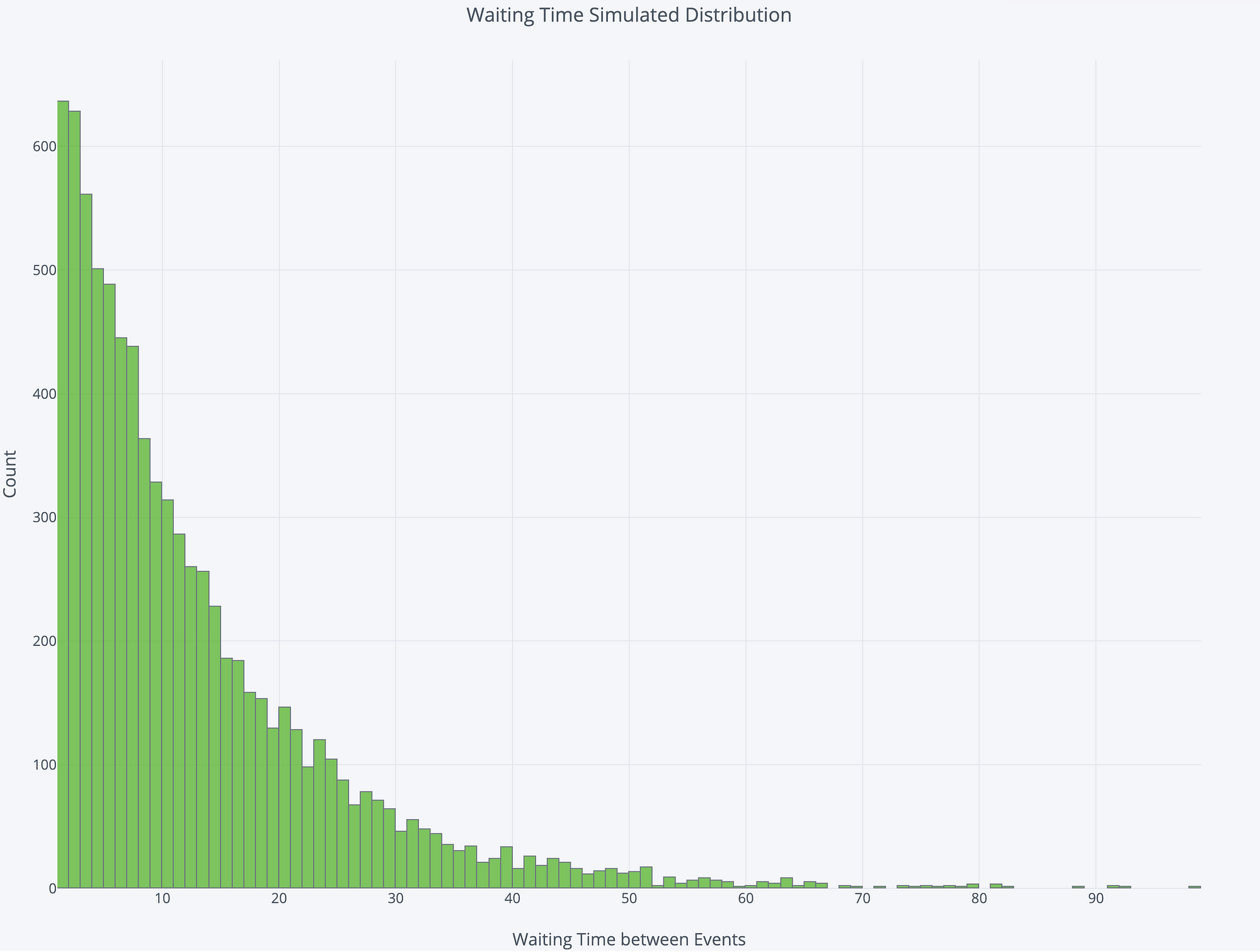

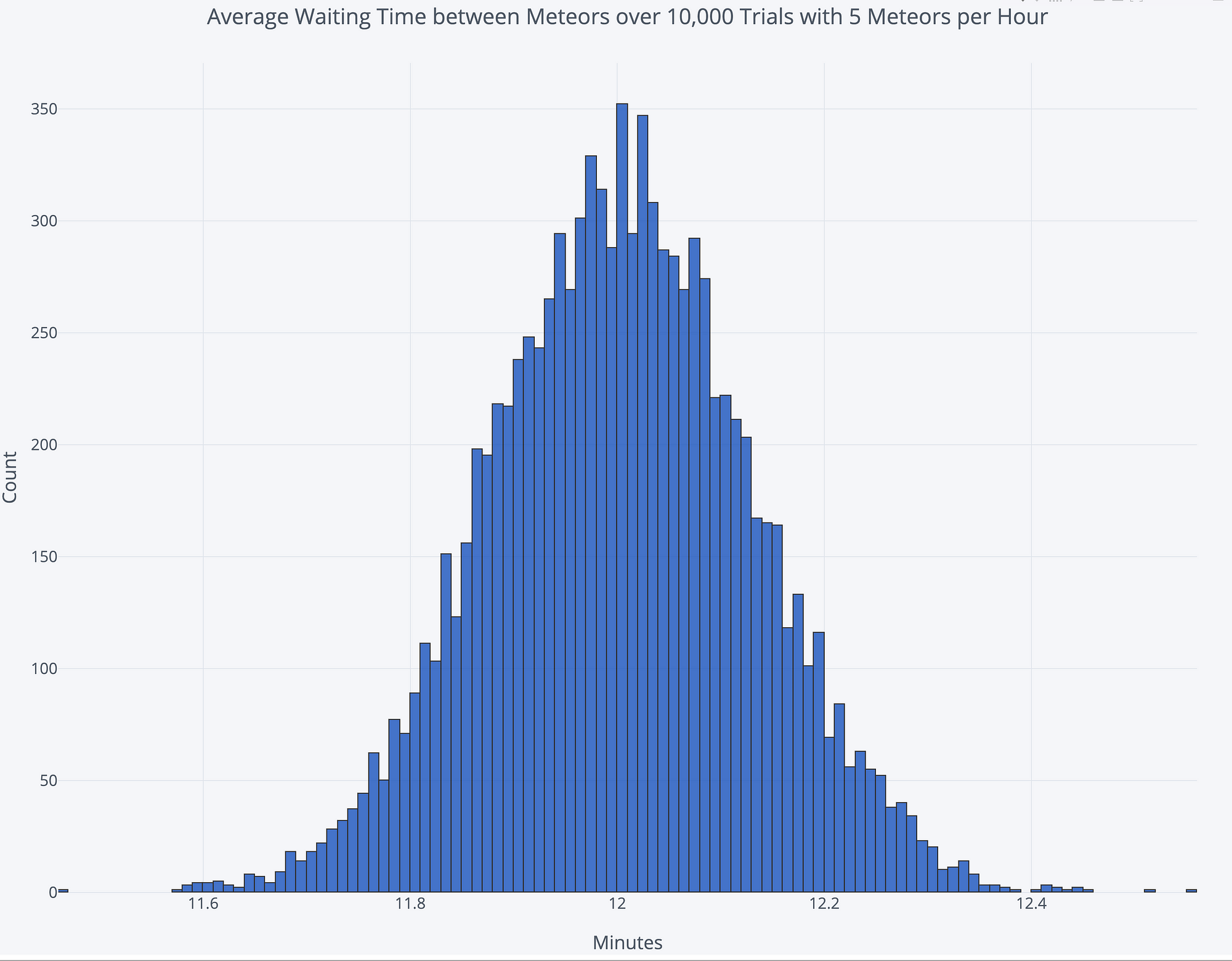

To visualize the distribution of waiting times, we can once again run a (simulated) experiment. We simulate watching for 100,000 minutes with an average rate of 1 meteor / 12 minutes. Then, we find the waiting time between each meteor we see and plot the distribution.

Waiting time between meteors over 100,000 minutes.

Waiting time between meteors over 100,000 minutes.

The most likely waiting time is 1 minute, but that is not the average waiting time. Let’s get back to the original question: how long can we expect to wait on average to see the first meteor if we arrive at a random time?

To answer the average waiting time question, we’ll run 10,000 separate trials, each time watching the sky for 100,000 minutes. The graph below shows the distribution of the average waiting time between meteors from these trials:

Average waiting time between meteors with simulated trials.

Average waiting time between meteors with simulated trials.

The average of the 10,000 averages turns out to be 12.003 minutes. Even if we arrive at a random time, the average time we can expect to wait for the first meteor is the average time between occurrences. At first, this may be difficult to understand: if events occur on average every 12 minutes, then why should we have to wait the entire 12 minutes before seeing one event? The answer is this is an average waiting time, taking into account all possible situations.

If the meteors came exactly every 12 minutes, then the average time we’d have to wait to see the first one would be 6 minutes. However, because this is an exponential distribution, sometimes we show up and have to wait an hour, which outweighs the greater number of times when we wait fewer than 12 minutes. This is called the Waiting Time Paradox and is a worthwhile read.

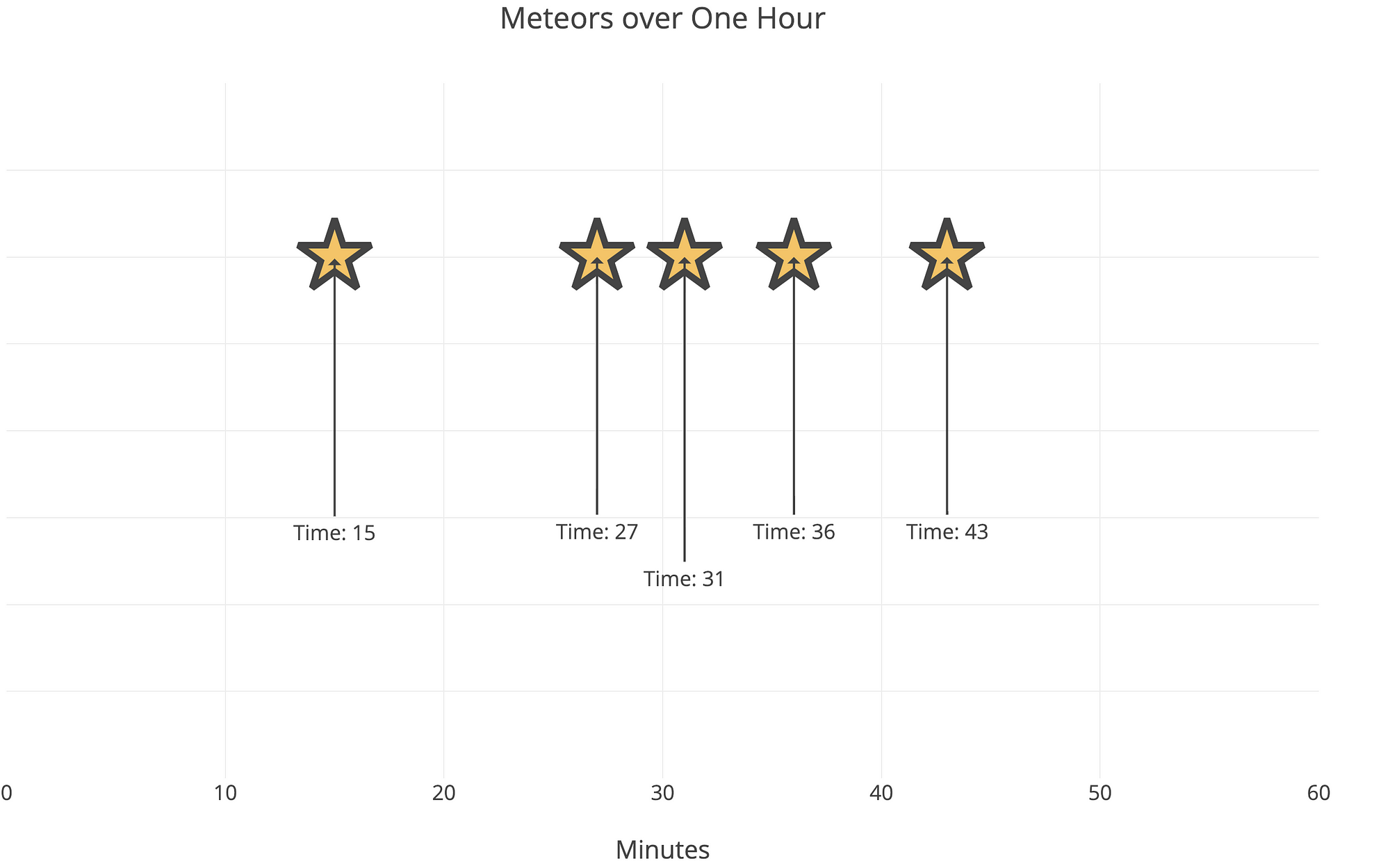

As a final visualization, let’s do a random simulation of 1 hour of observation.

Simulation of 1 Hour

Simulation of 1 Hour

Well, this time we got exactly what we expected: 5 meteors. We had to wait 15 minutes for the first one, but then had a good stretch of shooting stars. At least in this case, it’d be worth going out of the house for celestial observation!

Notes on Poisson Distribution and Binomial Distribution

A Binomial Distribution is used to model the probability of the number of successes we can expect from n trials with a probability p. The Poisson Distribution is a special case of the Binomial Distribution as n goes to infinity while the expected number of successes remains fixed. The Poisson is used as an approximation of the Binomial if n is large and p is small.

As with many ideas in statistics, “large” and “small” are up to interpretation. A rule of thumb is the Poisson distribution is a decent approximation of the Binomial if n > 20 and np < 10. Therefore, a coin flip, even for 100 trials, should be modeled as a Binomial because np =50. A call center which gets 1 call every 30 minutes over 120 minutes could be modeled as a Poisson distribution as np = 4. One important distinction is a Binomial occurs for a fixed set of trials (the domain is discrete) while a Poisson occurs over a theoretically infinite number of trials (continuous domain). This is only an approximation; remember, all models are wrong, but some are useful!

For more on this topic, see the Related Distribution section on Wikipedia for the Poisson Distribution. There is also a good Stack Exchange answer here.

Notes on Meteors/Meteorites/Meteoroids/Asteroids

Meteors are the streaks of light you see in the sky that are caused by pieces of debris called meteoroids burning up in the atmosphere. A meteoroid can come from an asteroid, a comet, or a piece of a planet and is usually millimeters in diameter but can be up to a kilometer. If the meteoroid survives its trip through the atmosphere and impacts Earth, it’s called a meteorite. Asteroids are much larger chunks of rock orbiting the sun in the asteroid belt. Pieces of asteroids that break off become meteoroids. The more you know!.

Conclusions

To summarize, a Poisson Distribution gives the probability of a number of events in an interval generated by a Poisson process. The Poisson distribution is defined by the rate parameter, λ, which is the expected number of events in the interval (events/interval * interval length) and the highest probability number of events. We can also use the Poisson Distribution to find the waiting time between events. Even if we arrive at a random time, the average waiting time will always be the average time between events.

The next time you find yourself losing focus in statistics, you have my permission to stop paying attention to the teacher. Instead, find the relevant equations and apply them to an interesting problem. You can learn the material and you’ll have an appreciation for how stats helps us to understand the world. Above all, stay curious: there are many amazing phenomenon in the world, and we can use data science is a great tool for exploring them,

As always, I welcome feedback and constructive criticism. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will.